The Maris Review, vol 67

I didn't mean to read two new novels about artistic muses and obsession this week, but I'm glad I did.

What I read this week

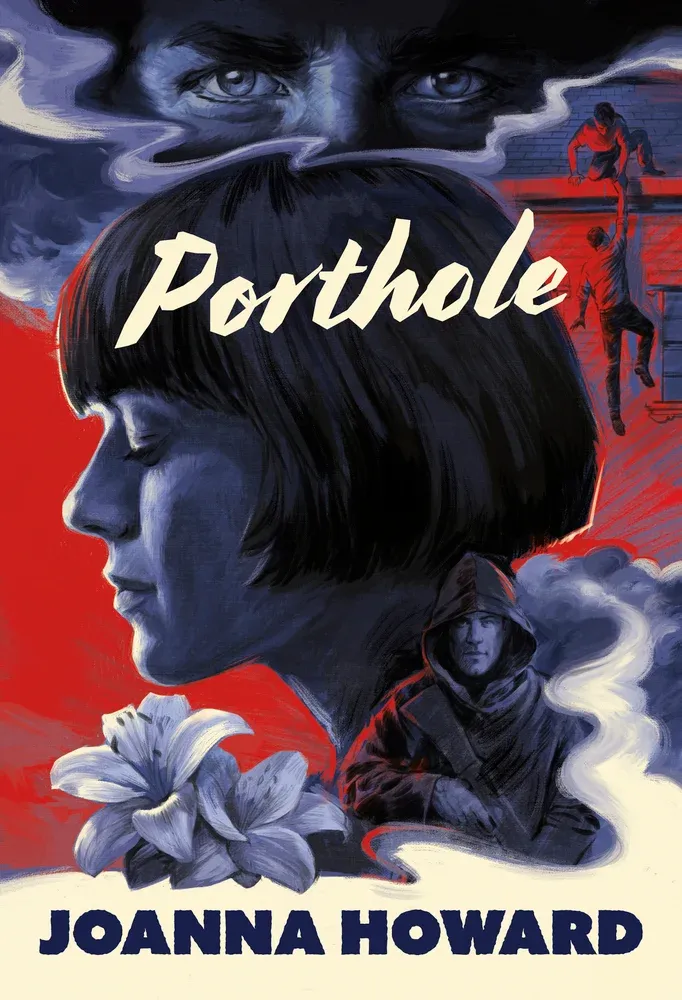

Porthole by Joanna Howard

I wish more people were talking about this book because it's the kind I'd like to discuss, to gather different opinions, to read others' interpretations. So maybe you'll read now and join me?

Porthole is the story of Helena Désir, a delightfully pretentious and narcissistic art house cinema auteur, a women who is very much an art monster in the masculine sense of the word. Her art comes first; the people in her life are mere tools she uses to make her art. Or are they? The subject matter of Helena's films are also masculine in the macho sense of the word: they lack sentimentality and are big on violence, and also her protagonists are always men. There's barely mention of actresses at all. I understand that Helena's films and some of her biography indicate that she's an Agnes Varda type, but I don't know enough about French New Wave cinema to say much more than that.

After an accident on the set of her newest film kills the films star (her latest muse, Corey) Helena is sent by her studio to heal her "psychic exhaustion" at Jaqith House: part asylum, part spa, part commune. We experience Jaqith House as an extended fever dream where reality is fluid and physical descriptions tend toward the maximalist. If Helena prefers to use physical gestures and appearances rather than dialog to develop the characters in her films, then at Jaqith House her interior and exterior get all mixed up and the thoughts in her head take over. Is she thinking this particular thought or speaking it aloud to other sufferers of psychic exhaustion? Often she's not quite sure. Is Helena a genius or a hack or both? That seems like the book's main mystery.

Throughout Helena's journey at Jaqith House we get the backstory on the three men who starred in her films, with all of whom she had tumultuous personal relationships. God, how I hate that it feels like a feminist act simply to be able to see a character who enjoys her role as puppet master of a group of men. Take that, Woody. Take that, Polanski. If Joanna Howard's prose does not feel as cold and precise as Helena's films, then it can still feel raw and unflowery in the best way. Just about every book that takes place in the theater or film world is about the parts we play, but the deconstruction of Helena is a particularly fruitful jumping off point to contemplate what a book allows an author to express that a film simply could not (and vice versa of course).

Lonely Crowds by Stephanie Wambugu

There have been so many excellent novels about friendship recently (and a few duds, which I won't name!) and Lonely Crowds is a really lovely addition to the canon. Do I see a touch of Ferrante's Neapolitan novels in there? It's difficult not to when the subject matter involves the friendship, starting from childhood, of two ambitious and obsessive women. But I was particularly reminded of the sexual chemistry in Zadie Smith's Swing Time, a novel in which two girlhood friends who enjoy dancing grow up both together and separately but only one succeeds (sort of, briefly) as a dancer.

The narrator of Lonely Crowds is Ruth, a daughter of strict Kenyan immigrants who falls in love at first sight (sorry to use a romance novel term, but it really is the best way to describe what happens when Ruth goes to pick up her Catholic school uniform in her quiet town in Rhode Island and sees Maria, the only other Black girl who will be in her class). Maria is an orphan who lives with her mentally ill aunt, and it doesn't take long before she spends most of her time at Ruth's home.

If Maria is the more outgoing girl, the one less bound by the rules, then Ruth is happy to lose some of her innocence at Maria's hand. Their will-they-or-won't-they dynamic of their college years at Bard turns into something else as they move to New York City and immerse themselves in the art scene of the 1990s (the author Stephanie Wambugu was born in the late 1990s but she writes about the time so convincingly) even as they go separate ways.

My big wish for Lonely Crowds is that it contained more about the actual making of the art, but I also understand how unreasonable such a wish is. In this novel the art is not the thing. In Lonely Crowds the art is Maria. Ruth's objectification of Maria is more vivid than any of the other art she makes. We get to know and to love Ruth through her passion for Maria even as she's ambivalent about the rest of her life. Over the course of the novel Wambugu teases out, for me at least, a slowly dawning realization that Ruth may be an unreliable narrator when it comes to her friend. Ruth will feel familiar to anyone who's ever been obsessed with someone else: when your obsessions are so very clearly more about you and your own hangups (about your family, your ambitions, your career) than they are about the object of your pining.

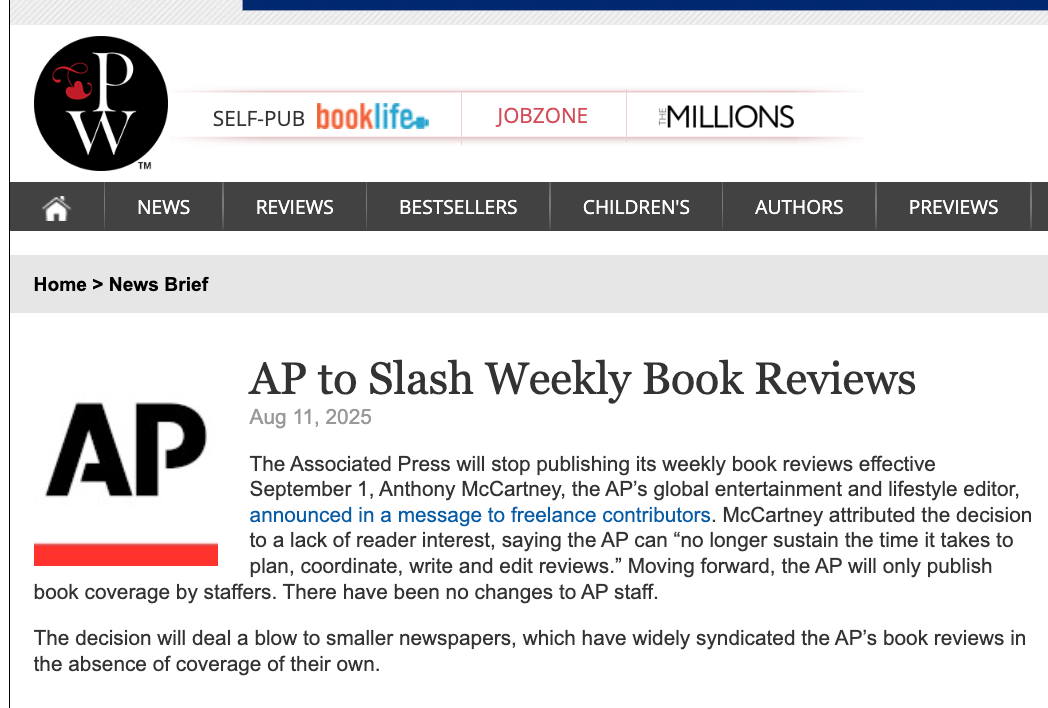

More bad news in the world of book criticism

The news that the AP will no longer be using freelance critics for weekly book reviews was a blow this week. Especially because my essay collection didn't get reviewed very widely but my AP review got syndicated all over the place. I feel like I made it by the closest margin, and lots of other authors are really going to miss out.

What do we do when traditional reviews go away? I really appreciated Richard Brody's recent New Yorker column, "In Defense of the Traditional Review", written in response to the news that the New York Times was getting rid of some of its most tenured and insightful reviewers in favor of, according to editor Sia Michel's internal memo, "trusted guides" who would comment on culture by using "new story forms, videos and experimentation with other platforms" that "go beyond the traditional review." It feels too cliché to even mention that this is basically just a good old fashioned pivot to video.

I'm gonna just block quote Brody here because yes to all of this:

What’s lost in such diluted coverage is proper assessment of the basic cultural unit. Just as the individual work is what individual artists—whether directors, actors, crew, or producers—create at a given moment, it’s also how viewers fundamentally seek out works: one at a time. And what a review embodies, above all, is one viewer’s experience of it. The essence of the review is evaluation, which of course doesn’t imply the crude simplicity of a thumbs-up or thumbs-down. (There’s a special pleasure for critics in hearing from readers who are unsure whether to take a particular review as positive or negative.) Even as a review confronts a work’s commercial role, it also embodies the opposite—a work’s potential vastness, the possibly overwhelming and transformative impact of a single viewing or listening.

I've slowly and steadily, and then very quickly, watched former homes for book criticism go away. What belongs in its place? I have no idea. You are reading this newsletter but I firmly believe that newsletters won't save us. You are here most likely because you care about books: so what would you like to see? What kind of book coverage moves you? (But also please don't say video; I'm so incompetent at video.)

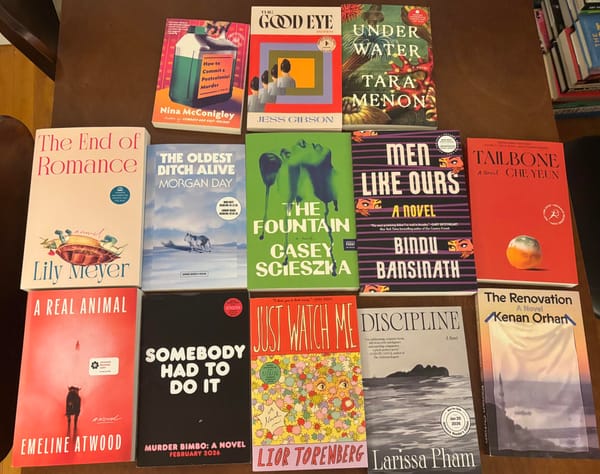

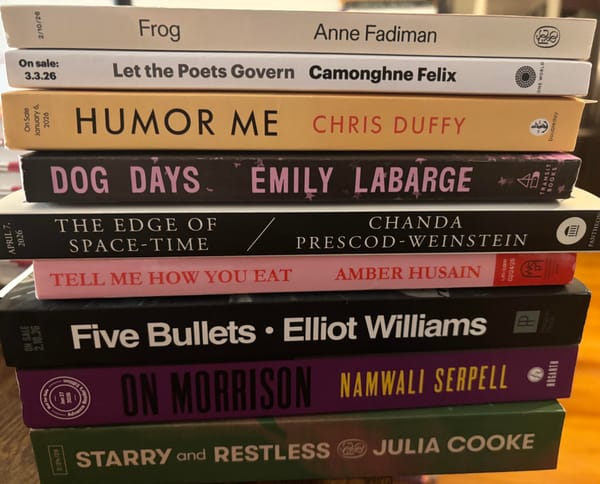

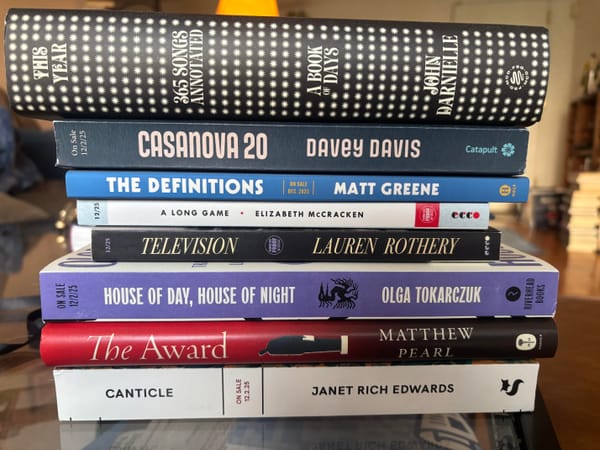

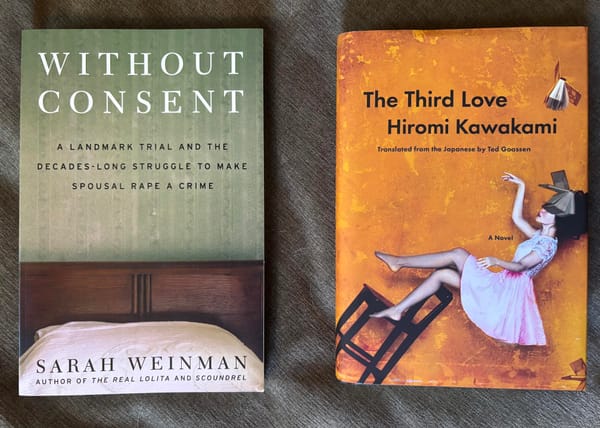

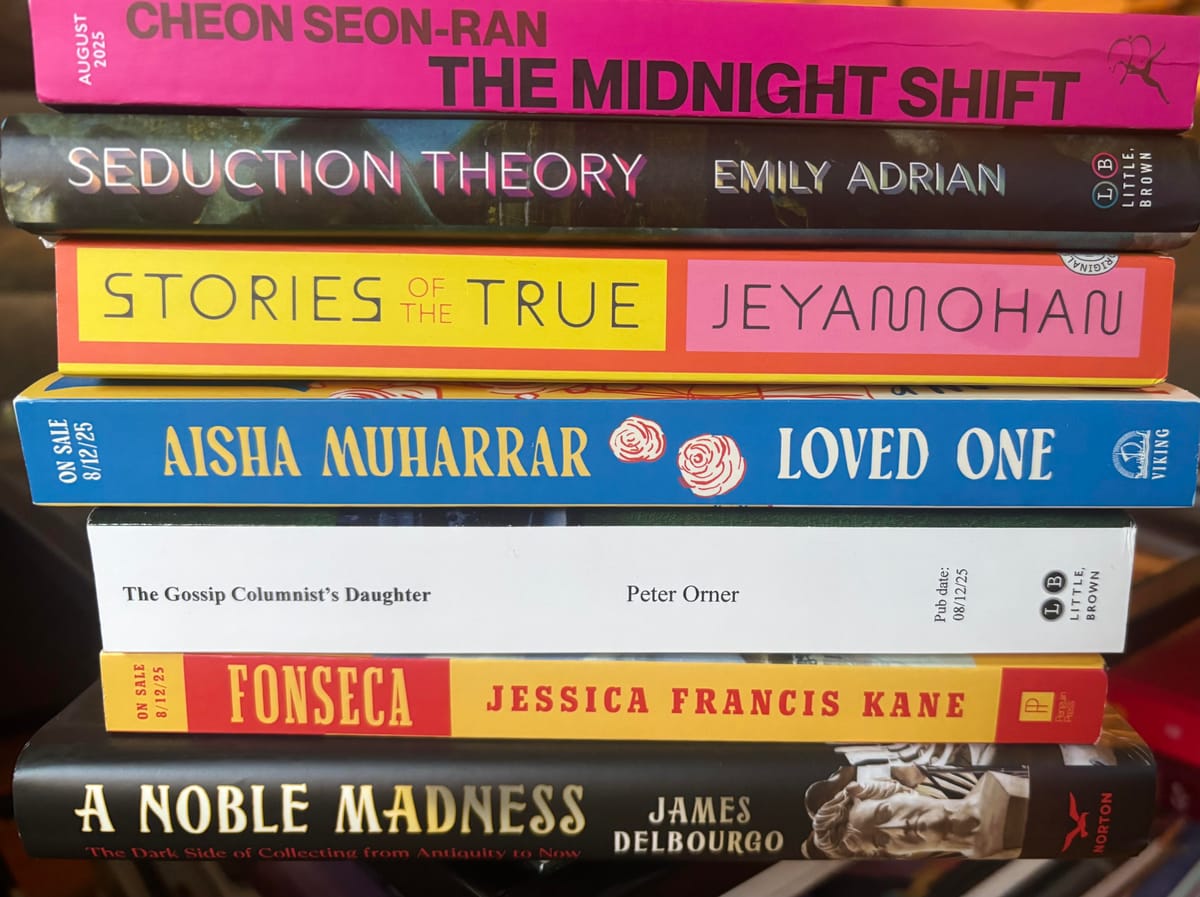

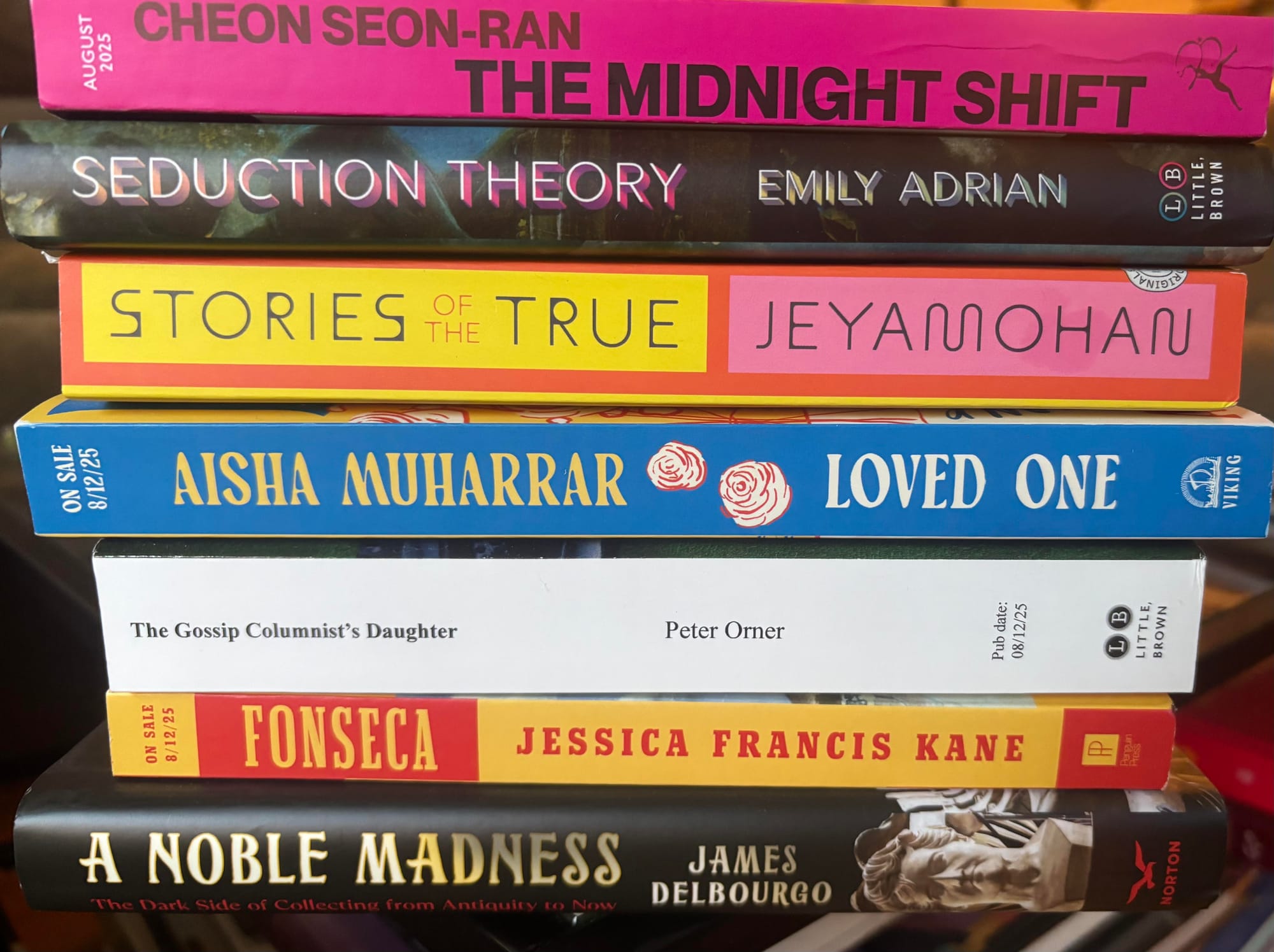

New releases, 8/12

The Midnight Shift by Cheon Seon-Ran

Seduction Theory by Emily Adrian

Stories of the True by Jeyamohan

Loved One by Aisha Muharrar

The Gossip Columnist's Daughter by Peter Orner

Fonseca by Jessica Francis Kane

A Noble Madness: The Dark Side of Collecting from Antiquity to Now by James Delbourgo

Both/And: Essays by Trans and Gender-Nonconforming Writers of Color edited by Denne Michele Norris

The Gods of New York: Egotists, Idealists, Opportunists, and the Birth of the Modern City: 1986-1990 by Jonathan Mahler

The Right of the People: Democracy and the Case for a New American Founding by Osita Nwanevu