The Maris Review, vol 71

In which I discuss books by a very distant relative and an all-time favorite author.

What I read this week

A Truce That Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews

Miriam Toews is one of my favorite writers, and All My Puny Sorrows is one of my favorite novels. Like, top 10 of all time. The novel, about a musician with a suicidal sister who she is desperate to support in any way she can, changed my understanding of what love is. As I wrote in Vulture's Attempt at a 21st Century Canon, it's a profoundly tender love story about deep despair: "Sorrows brims with jokes that are real and plentiful and well-earned, as well as a keen sense of what joy looks like even in the darkest of times."

I profiled Miriam back when Women Talking first published (RIP BuzzFeed News), and to prepare for our talk I read her entire backlist which is mostly comprised of autobiographical fiction. All of her fiction, in some form or another, grapples with her Mennonite background (all of her backlist) the loss of her sister (All My Puny Sorrows) and her father (Swing Low) by suicide, and celebrates her extraordinary mother (Fight Night). So the topics in Miriam's very first memoir feel familiar, like meeting up with old friends and getting right back into the groove of how you used to relate to each other. I might not recognize all of the factual details she refers to, but I am very familiar with the feelings – both tender and bleak – that came flooding back (incredible that last week I read Arundhati Roy's memoir and had the same experience, as if both authors had written nonfictional guides to unlocking their fiction).

A Truce That Is Not Peace is centered around one important question: Why does Miriam Toews write? The book is not at all a craft guide, but it is a testament to how to process extraordinary grief and still find the will to live. Anyone who's read any of Miriam's previous fiction might already guess that writing is an integral part of that process, but the joy of the book is going along with Miriam as she attempts to answer the question, reckoning with memories and old letters and other texts that have made her want to write in the first place.

I'll leave you with just a taste of how Miriam describes what writing is.

"But between the beginning and the end of civilization, the Parthenons and the pelting of stones, is the narrow corridor, the spit of land, where writing lives. After disillusion--but just after--and before the end of relief--but quite a bit before--is where writing lives, where the soul (douchebag word, soul? Recently a private equity investor asked me if I thought I had a soul and I couldn't stop laughing) or the writer floats, not as in a regatta, sun sparkling on water, but so precariously."

They All Came to Barneys: A Personal History of the World's Greatest Store by Gene Pressman

Okay, there's a bit of a story here. A few years ago I wrote about how I watched from afar as Barneys, the beloved department store owned by my very distant relatives, went bankrupt and was then liquidated. Barney Pressman was my great-grandfather's brother. I am not close to the Pressman family by any means. I remember meeting Freddy (Barney's son and Gene's father) in the store at 17th Street when we still got a discount there in the 1980's, and I remember my mother's reverence for him. When the article was published Gene sent me an angry email saying that I was not part of his family, and I was like, yeah I know. I preferred when the old Barney's location became a Loehmann's and I could afford to shop there.

A revised and expanded version of that essay made it into my book, and the story of the Pressmans became more of a way to examine what I call the Jewish American Dream in which the first generation makes something, the second generation builds it up, and the third generation squanders it. I got the idea when reading Patrick Radden Keefe on the Sacklers and seeing so many similarities (the Pressman family never killed anyone, to be clear). Of course it's not that simple to measure success or failure by generational delineations and certainly the fall of Barneys is not Gene's fault alone. As he adamantly insists.

This is all to say that I read Gene Pressman's history of the store's rise and fall with great interest. I am sorry to admit this, but I was absolutely delighted by how pompous he sounds throughout the book. He sounds like how we would have sounded in my head, entitled and brash and without a hint of self-awareness even as he acknowledges time and time again that he was born on third base. He had a ghostwriter, and that ghostwriter made a choice for how to portray him, and I salute them both.

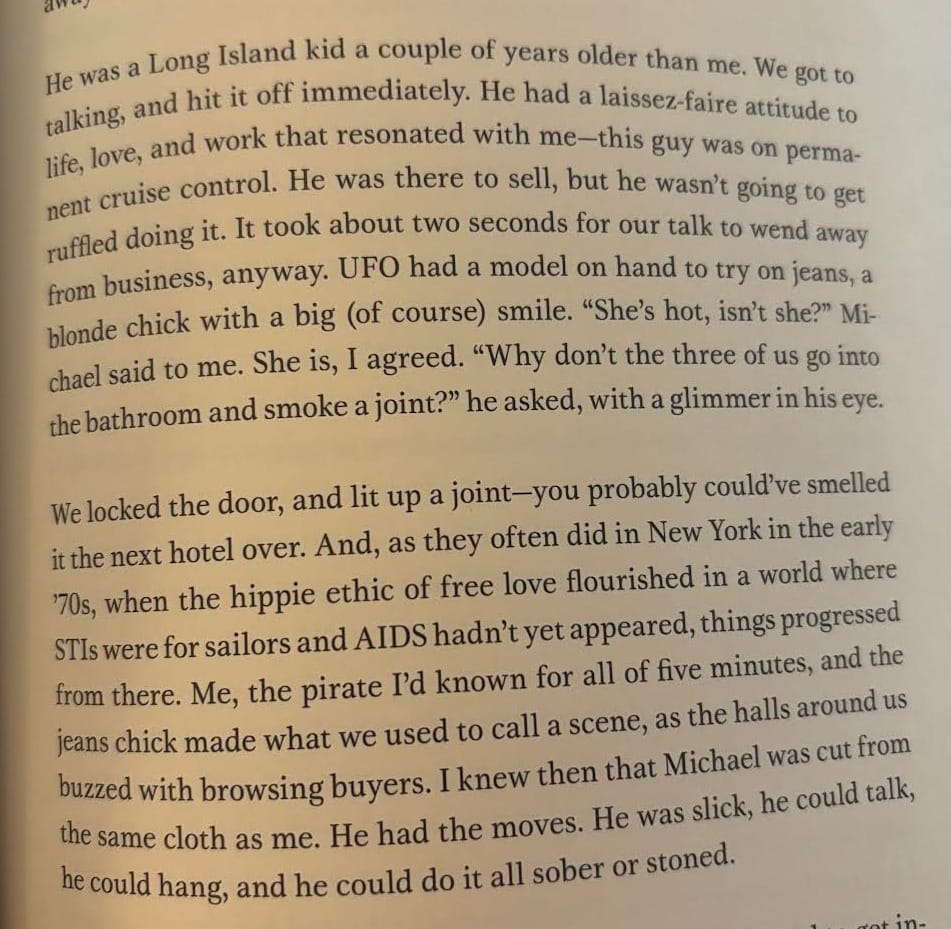

Here's just a sampling:

So much of the book is about Gene's excesses: fucking models and doing blow in the 1970s before it was all over New York and then moving on to quaaludes by the time of the disco era. It adds to the mood even more that Gene is now 74 years old and living in Palm Beach with his second wife and their 6 year-old daughter.

But I loved so many of Gene's stories about Barneys, and I wish he had spent a little more time examining the short period after college when he, the hard-partying playboy, lived with his grandfather on the Upper East Side and a chauffeured limo would pick them both up every morning and bring them to the store. That is a plot for a sitcom I would watch.

Of course Gene is the kind of nepo baby turned employer who referred to staff as "our people." So many of his insights about how Barneys went from a major men's retailer to a womenswear destination in the 1980s sounds like "women be shopping." Men are from Mars, etc etc. Still, Gene has some great stories. And I loved how he talked about his father, Freddy. Freddy, who made Barneys a destination for fashion (one of Freddy's big successes was discovering this Italian designer named Giorgio Armani and licensing the right to sell his stuff in the US). Gene was there for all the years when Barneys was one of the coolest spaces in the world, where artists and creative types and models and celebrities would mix, and it's so fun to be there with him.

The book ends with Gene's thoughts on the digital age, about how choosing what to sell based simply on data is soulless. How giving people exactly what they want when they want it is less impressive than exposing customers to something entirely new and making them love it.

"Online, everyone has an opinion, and no one's an expert. The only expert is data, and everyone follows the analytics. If something sells on day one, they buy a hundred more; if something doesn't, they never touch it again. But that's not merchandising. It's a recipe for a Stepford store where everyone will end up looking the same. Head-to-toe shit!

There is no good art or good fashion without taking risks, says Gene. It's kind of nice to realize that on this point we are aligned. Maybe we do have something in common besides a little bit of family blood after all.

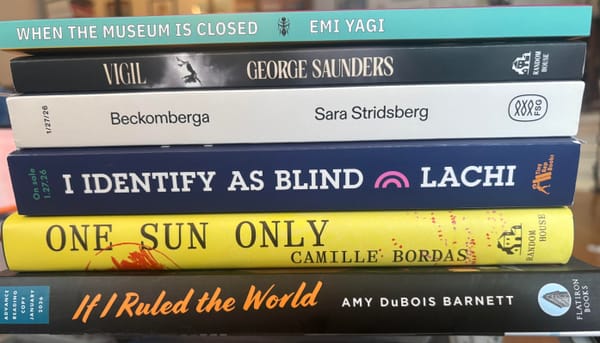

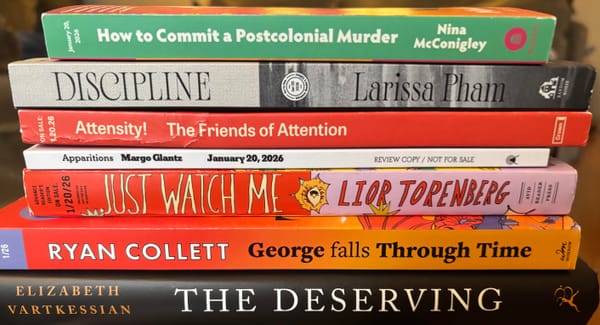

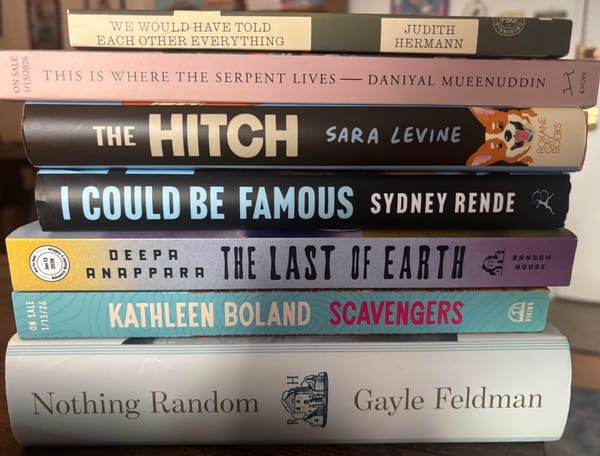

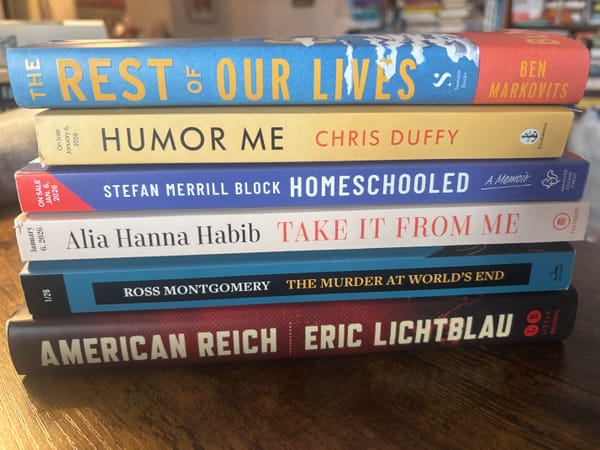

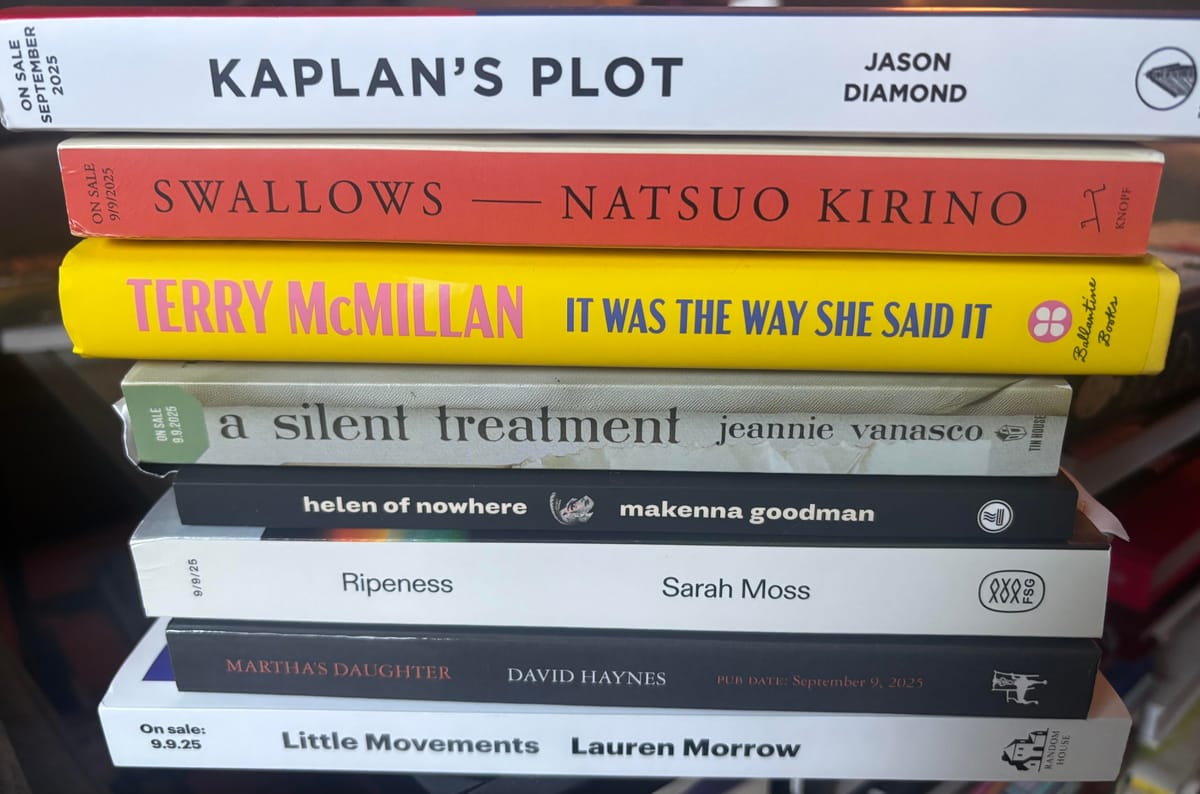

New releases, 9/9

Kaplan's Plot by Jason Diamond

Pay extra attention to this one. I love this novel so much and I'm so proud of Jason for making such a splash with his fiction debut. I'll be writing more about it later, but just let me say right now: happy pub day to your wonderful novel, Jason!!

Swallows by Natsuo Kirino

It Was the Way She Said It by Terry McMillan

A Silent Treatment by Jeannie Vanasco

Helen of Nowhere by Makenna Goodman

Ripeness by Sarah Moss

Martha's Daughter by David Hynes

Little Movements by Lauren Morrow

Middle Spoon by Alejandro Varela

This Is for Everyone: The Unfinished Story of the World Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee

Dark Renaissance: The Dangerous Times and Fatal Genius of Shakespeare's Greatest Rival by Stephen Greenblatt