The Maris Review, vol 83

It's anticipation time...

What I read this week

What We Can Know by Ian McEwan

When I say What We Can Know is Ian McEwan's best novel since Atonement, I should admit that I haven't been meticulous about keeping up. I believe I had two McEwan DNFs (did not finish) over the past decade or so. But still. There is a spirit of narrative playfulness in this one, it's profound but it's also fun, which goes a long way in my book.

It's the year 2119 and on college campuses the humanities are in trouble. Why, the students think, should they bother learning about the poetry and philosophy and daily habits of a bunch of dead people who had nothing but contempt for the generations to follow? Thomas Metcalfe is the professor who wants to change their minds. He teaches a class on literature from 1990 to 2030, 90-30 for short, before the Derangement when global warming and nuclear fallout and just about every kind of dystopian disaster towards which we seem to be hurdling has reshaped the world. The students in 90-30 can't help but look back on their ancestors with derision, but Metcalfe remains obsessed with a small circle of literary elite organized around a great poet, Francis Blundy, and his wife, Vivian. Francis's crowning achievement was a work that was lost to time but venerated for a century all the same. And so it is that the world building in the novel takes place through the guise of course curriculum and scholarly work.

We follow Metcalfe through his travels around the archipelago that was once the UK (much of it is under water now) to research the mystery of the great poem and whether it might still exist. The second half of the book is told from Vivian's point of view, and it's the second best tonal reversal in literature in 2025 after the one in Audition. It's an excellent commentary on our data-fueled present time with overstuffed archives (books and journals and emails but also social media and phone videos and other digital detritus) versus the parts of history that can only exist offline.

Caucasia by Danzy Senna

I've spent a lot of time over the past few weeks reading debut fiction for this year's Young Lions Fiction Prize for the New York Public Library. I won't talk about any of the books here, not until winners are announced in the spring. But all this reading has really got me thinking about what an "assured" debut means to me, because you see that word everywhere in describing new voices in fiction. To me, "assured" means having a decisive point of view, a lack of reliance on cliches, and a controlled grasp on figurative language. The debuts I read varied in "assuredness," and they made me want to read one that I know had been successful, or at least according to critics.

As I expected Caucasia is assured as hell. I loved Danzy Senna's two previous novels, Colored Television and New People, so it was only right that I'd go back and read her celebrated debut published in 1998. Throughout her career Senna's work has been preoccupied with what it means to be of mixed race and what happens to identity when you're stuck between worlds. In Caucasia I could see a bit of an origin story.

Senna's debut tells the story of Birdie, a young protagonist who is neither too precocious nor too naive, which is a tough line to walk. Birdie and her big sister Cole grow up in 1970s Boston with their Black father and white mother amid the busing crisis and civil unrest. After the breakup of their parents' marriage, Birdie's darker sister goes to live with her father while Birdie is left with her radical mother who takes her on the run, Running On Empty style. Birdie's entire young life then revolves around her mother's attempt to disappear and start again fresh. And so Birdie begins to pass as a Jewish girl, big Star of David necklace and all, and is divorced from her Black lineage entirely. Add to that the regular pains of adolescence, and it's no wonder that Birdie is headed toward an existential crisis. She may be isolated and uncertain, but she makes for wonderful company.

A note: the incredible audiobook narrator January Lavoy is the only one I would trust to do all of the voices related to the Boston busing crisis of the late 1970s without descending into caricature.

Other favorite debuts

The Giant's House by Elizabeth McCracken

The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell

Severance by Ling Ma

Disappearing Earth by Julia Phillips

Luster by Raven Leilani

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

Atmospheric Disturbances by Rivka Galchen

The Parisian by Isabella Hammad

What Belongs To You by Garth Greenwell

Nobody Is Ever Missing by Catherine Lacey

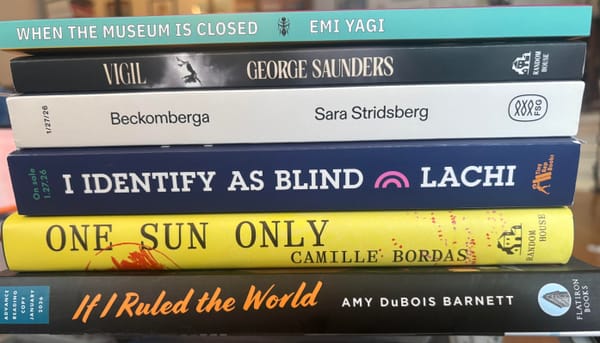

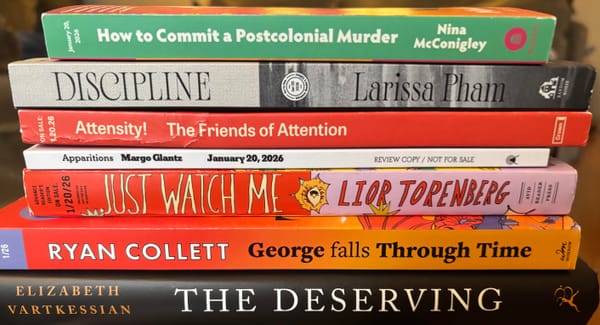

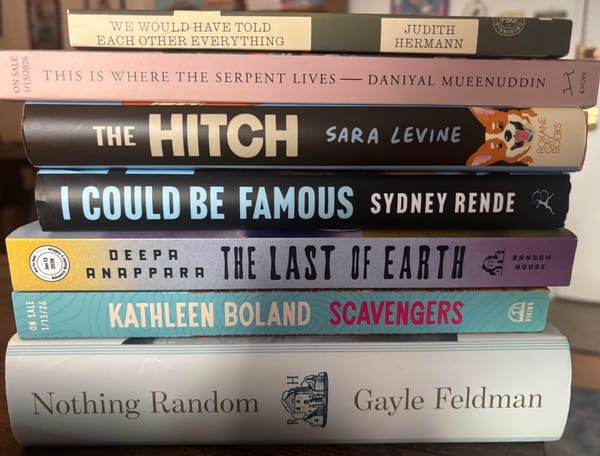

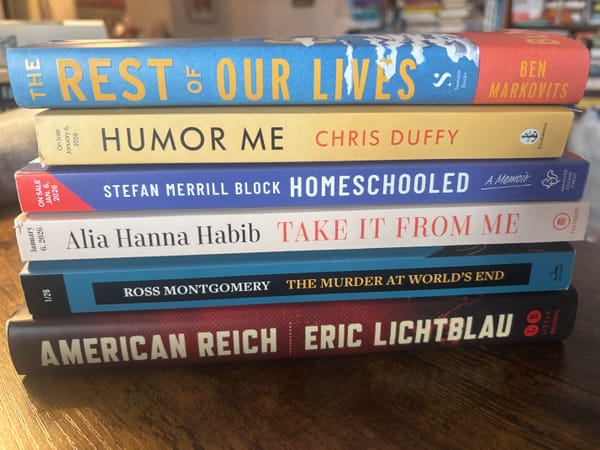

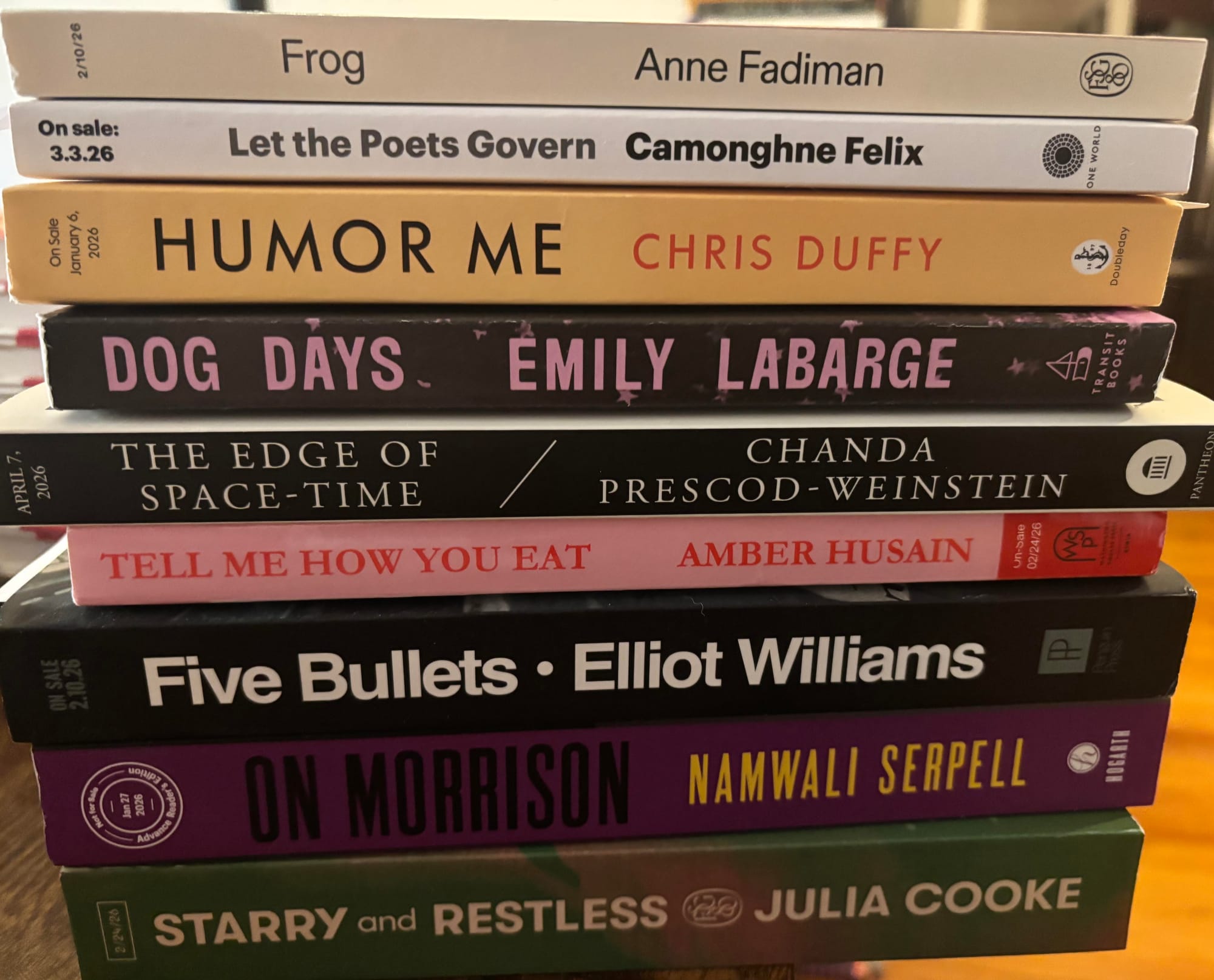

Most anticipated nonfiction of 2026

There aren't many notable releases left in December, so for the next couple of weeks I'm going to be doing a little 2026 preview instead. First up is nonfiction I'm excited about in 2026. Note: these are just the galleys I have in my home. There are so many other nonfiction books I'm eager to cover in the new year, but they just aren't on hand yet.

Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman

Let the Poets Govern: A Declaration of Freedom by Camonghe Felix

Humor Me: How Laughing More Can Make You Present, Creative, Connected, and Happy by Chris Duffy

Dog Days by Emily LaBarge

The Edge of Space-Time: Particles, Poetry, and the Cosmic Dream Boogie by Chanda Prescod-Weinstein

How It Feels to Be Alive: Encounters with Art and Our Selves by Megan O'Grady

Tell Me How You Eat: Food, Power, and the Will to Live by Amber Husain

Five Bullets: The Story of Bernie Goetz, New York's Explosive '80s, and the Subway Vigilante Trial That Divided the Nation by Elliot Williams

On Morrison by Namwali Serpell

Starry and Restless: Three Women Who Changed Work, Writing, and the World by Julia Cooke